Engaging Miksang: The Foundation Practices of Contemplative Photography Part II

Shambhala Online Zoom Class with Miksang Practitioner Ivette Ebaen

4 Consecutive Sundays: June 20th, 27th, July 11, July 18, 2021.

10-12 noon Philadelphia EST

3-5pm GMT Ireland & UK. 4pm-6pm Netherlands & Germany

8-10 Participants. Pre-requisite: Envisioning Miksang: The Foundation Practices of Contemplative Photography Part I or permission from instructor

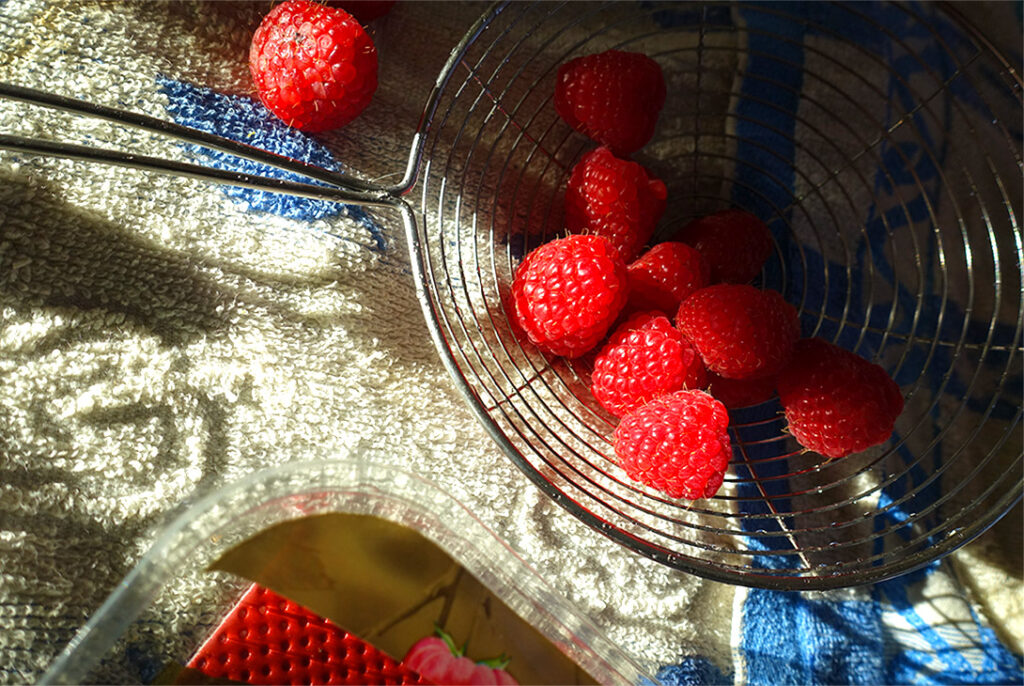

In the second part of our Miksang contemplative practice practitioners delve into the heart of their photography. We gently focus on strengthening our understanding via the flashes of perception and synchronization practices guided by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s Dharma Art teachings. We engage with our ordinary personal world anchored in an intimate way. We practice in relationship, being present to experience the phenomenal world as it is by letting go and letting be.

In this stage of our practice images are no longer perceived and photographed in the abstract sense of the word as just colour-as-colour or patch-of-light, without the form they highlight. This time we follow the world of shapes, their texture and color along with light, shadow, pattern, etc., etc. We begin to see how what we practice to perceive composes an equivalent image that is visually appreciated and pulsates to the beat of our individual hearts.

Join Miksang practitioner/teacher/photographer Ivette Ebaen for the second series of online Nalanda Miksang foundational courses hosted by the Philadelphia Shambhala Meditation Center.

To view Ms Ebaen’s work please visit her website: www.purevision.photography

For further information about the program, contact Program Coordinator Barbara Craig at [email protected]

Supported Tuition: $75.00 Program Tuition: $125.00 Patron: $165.00

To register please prepay tuition to save your seat in this class at the Philadelphia Shambhala website: https://philadelphia.shambhala.org/

Testimonials:

“What a wonderful class on Miksang we had. The zoom format worked well and the group was able to get to appreciate each other’s understanding and each person’s process creating the images. Ivette brought us to understand how to use Miksang photography as a Way, a path to open to the brilliance of everyday perception…I got tears in my eyes today as I understood why contemplative photography can be a dharma practice, and the profound teaching in dot-in-space.” A.M. USA

“Following the Miksang course with Ivette has been an incredible enriching experience for me. By practising Miksang, it is like you receive a new pair of ‘glasses’ to view the world with, one that opens up a whole new look on reality and brings a lot of new wonders to life…” P.R. NETHERLANDS

“I had read about Miksang photography prior to taking a class with Ivette Ebaen but really didn’t quite understand the essence of the practice. Studying with Ivette however has opened my eyes in more ways than one. She is able to convey the Miksang approach in a profound and gentle way…Ivette’s example photos show me the essence of Miksang in a nonverbal way and I have learned that a photography can be a visual aid to meditation, something I had never considered before…” K.J. USA

BIO: Ivette Ebaen is a professional exhibiting photographer; Miksang Practitioner and Certified Teacher, with a B.A. in Fine Arts and an M.A. Transpersonal Studies/Psychology. She is a member of Shambhala International, and Miksang International. She currently teaches from and resides in the Republic of Ireland.

Recommended Reading:

True Perception: The Path of Dharma Art, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche

Heart of Photography: Way of Seeing Vol. II, Further Explorations in Nalanda Miksang Photography, John McQuade and Miriam Hall

Please bring your journal, digital camera to each class, charged batteries, USB Stick, empty SD card to upload your pictures on laptop or PC and share on Zoom. You will receive a Zoom link before the start of class.