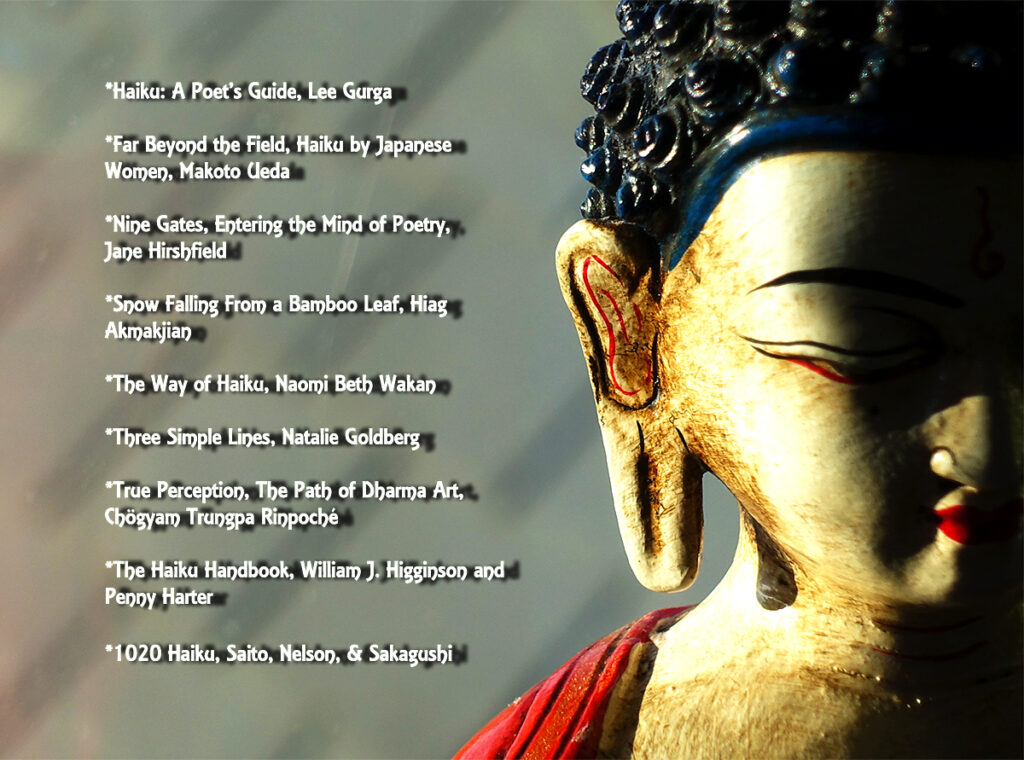

Miksang and Haiku: Two Aesthetic Forms of Being

One usually spends a certain amount of years learning a craft and creating art out of one’s craft. Occupation with one art is enough to consume any one lifetime. And here we are attempting to master haiku along with the Dharma Art of Miksang photography in one fell swoop.

So let us be kind to ourselves…

Rumor has it, there are no rules to writing haiku—yet there are. Of foremost importance is haiku’s poetic, aesthetic visual form expressed in three simple lines or as one line written vertically, as the Japanese prefer.

Custom, like the kigo (the seasonal word in haiku) has a reason for being. The voices of ancestral wisdom leave their imprint on the wind.

Regardless of what we’ve learned and heard other poets say, haiku has a definitive structure. Not that we have to follow every rule and recite them by heart. Yet this pathway grounds us on our journey across a selfless road of universal understanding.

The heart of haiku relies on the nature of experience and how receptive we are to perceive it. This means writing haiku that expresses life as we experience it, which contain words that show movement. This means choosing words that show life in stages of transition. Words that define the qualities of change because we know this to be true for ourselves. After-all, life is not a static or stagnant thing. Life lived is constantly in flux doing its rearranging, dying, regenerating; forever fluid; in a constant mode of creating creation.

A haiku along with its visual partner (the Miksang photograph) is an impression that expresses every moment as a moment in motion. If at all possible make this sentiment part of your photographic mindscape when creating the two.

When going out to photograph, let go of any intentions of how this journey will be. Free yourself of any personal expectations and assumptions. Relax into the awareness of what you hear, feel, smell, and see regardless of what your mind is saying.

Once aware, aware is all you are; this body/mind simply using and being all its sensations. You as awareness: looking, noticing then seeing with a quiet sense of mindlessness yet mindfulness, observing what is there.

While Nature just is, you and I have to relearn how to see and be in relationship to self and other. In one of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s lectures, he spoke about wanting to erase every article in the English language that referred and reaffirmed the existence of an ego “I”. Trungpa Rinpoché felt that this constant self-referencing alienated us from recognizing and realizing our authentic self. He wanted us to consider life lived free of, and liberated from the dictates of an assumed fictitious personality that we have come to idolize as Me, Myself and I.